William Hedgepeth "Inside the Hippie Revolution"

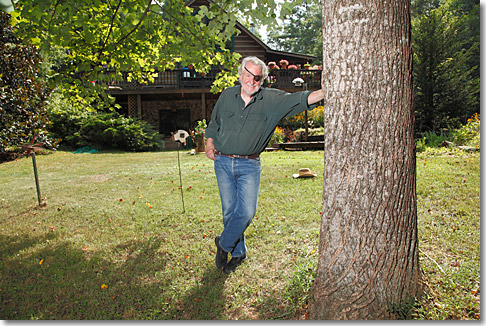

William Hedgepeth outside his home in the mountains of north Georgia, outside Blue Ridge. Hedgepeth went on to cover hunger in America, poverty, Native Americans, the changing South, and folk singers Joan Baez and Arlo Guthrie. |

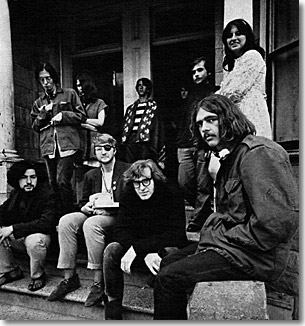

"A good pad is where you can live-in and love-in and turn on with your own communal 'family.' Editor Hedgepeth (holding hat) is shown with those of his family who were not immersed in the flowers of the park or panhandling on Haight St." |

|

William Hedgepeth was the youngest writer for LOOK when he was hired in 1967, so naturally he was asked to go "Inside the Hippie Revolution" in San Francisco. There had been a few newspaper articles about these strange, long-haired young people who seemed to be gathering in cities around the world. But no one knew that what happened in the Haight-Ashbury district in 1967 was to become known as the Summer of Love. Hedgepeth joined as many as 100,000 kids trying to create a counter culture based on rock music, art, creative expression, politics, drugs and sexual freedom. "I flew out from New York to San Francisco," Hedgepeth remembers. "Even as much as I had read about it, I was still mildly shocked when I got out of the cab and was sitting on the curb and I see two long-haired guys coming along. It kind of gave me a little bit of a shock." Within a few days, he found a group who wanted to form a commune in an old, littered house. What he documented was a cornucopia of drugs fueling a sense of revolution. "A radical change is taking place in this generation," Hedgepeth quoted the commune's leader Rick saying. "Middle-aged people just can't accept that their children are prophesying to them. The proof is that there's no communication between the generations." Hedgepeth saw straight people stuffed into cars touring the Haight behind locked doors, shooting pictures through tightly rolled up windows of the freaks on the street, "as if this were a tour through the reptile house at the zoo. "What the hippies say they are 'doing' in the more important sense is living creatively, experimenting with new styles of living and generally appreciating the wonder and changeability of human life. They have consciously 'dropped out,' or detached themselves, from what they consider the regimented, stultifying, dog-eat-dog 'games' of the straight world, and have redefined 'progress' and 'success' in purely human terms. No boundaries are drawn between art and life. Everyone is creative." Hedgepeth now admits that he didn't want to go home, didn't want to write the article. "Everything was going on there. Food. Drugs. Girls. Everything you could ask for. Music. The whole scene," he laughs now. "I did a good job of that in the piece! I did convince countless thousands of more people to go out there." Hedgepeth says the 60s were a pivotal time in our history. "Absolutely! Certainly so. I mean it was a crystallization of everything that had built up up to that point. The New Deal mentality reached its absolute high water mark there with Lyndon Johnson's programs, for example… It was at about that same time that a lot of working class people – as a result of protests of the war by mostly middle- and upper-middle-class college students – began to differentiate themselves from the young people who were demonstrating. Lyndon Johnson, when he signed the Voting Rights Act of 1965, he said, 'I've just given the South to the Republican Party for the next generation.' |

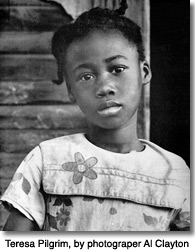

"The world is divided between those who view the future as an adventure versus those who view it as a threat. And that's really true," Hedgepeth says. William Hedgepeth went on to cover a wide range of issues for LOOK. He profiled folksingers Joan Baez and Arlo Guthrie. He wrote about "the New South … today a place where nothing whatever is the same." He covered Native American issues like the takeover of Alcatraz Island. And he covered poverty and hunger in America. Most memorably in the Christmas 1967 issue, he and photographer Al Clayton introduced Americans to "The Hungry World of Teresa Pilgrim."

When the story came out, there was an outpouring of sympathy for the family. "It had a record number of responses in terms of letters and people offering things," Hedgepeth remembers. "Tallulah Bankhead called me up, and she was moved by this." Small amounts of money came in and were forwarded to the family. Newspaper articles followed and Nathan appeared on the Joe Pyne TV interview show. Eventually Nathan was offered a job in Los Angeles and moved the family out there. I believe that Teresa and her siblings are still living in Los Angeles, and they would be a the top of my priority list as money for additional field work is raised. |

"I had me some bologna las' week," six-year-old Teresa told Hedgepeth. "Ain't had nair milk. Naw. we don' get much of th' won'erful things folks eats." Teresa, her father Nathan, mother Lerlene, brother "Pig" and sisters Dometa Jo and Lerlene were trying to survive on that day's food supply – flour, a quarter jar of instant coffee and an inch of rice in a cellophane bag. The Pilgrim family was one of thousands in the Mississippi Delta region who were existing one step away from starvation. Hedgepeth wrote that children like Teresa Pilgrim "who are neither statistics nor 'causes' – continue to exist on rice, grits, collards, tree bark, laundry starch, clay and almost anything else chewable."

"I had me some bologna las' week," six-year-old Teresa told Hedgepeth. "Ain't had nair milk. Naw. we don' get much of th' won'erful things folks eats." Teresa, her father Nathan, mother Lerlene, brother "Pig" and sisters Dometa Jo and Lerlene were trying to survive on that day's food supply – flour, a quarter jar of instant coffee and an inch of rice in a cellophane bag. The Pilgrim family was one of thousands in the Mississippi Delta region who were existing one step away from starvation. Hedgepeth wrote that children like Teresa Pilgrim "who are neither statistics nor 'causes' – continue to exist on rice, grits, collards, tree bark, laundry starch, clay and almost anything else chewable."